I'm nobody, so why should you believe me?

Well, Tom Verducci believes me.

In fact, he takes my work on pitching mechanics seriously enough that, on two occasions now, he has plagiarized my work.

And people generally don't steal things that they think are worthless.

Verducci Believes...

On the one hand, plagiarism is frustrating as hell.

On the other hand, plagiarism is validation; nobody steals something unless they think it's valuable.

And that's how I choose to take Tom Verducci's borrowing of my words, concepts, and work.

As validation.

Matt Harvey

In October 2010 I was updating my core piece on Matt Harvey's pitching mechanics and a number of related pieces. I was Googling around, looking for clues about the cues that were used to shape -- and that ruined -- Matt Harvey's arm action. One piece I came across was Windows Close Fast by Tom Verducci.

But today Harvey, like Yasiel Puig and Tim Tebow, is famous for being famous, not for compiling a superstar’s resume. He has thrown fewer innings, made fewer starts and won fewer games than Michael Pineda. He never has won 15 games, made 30 starts or thrown 200 innings. Tommy John surgery, thoracic outlet surgery and the mechanical compromises he made to throw harder have derailed his ascendency. It’s a common story in baseball these days in the pursuit of almighty velocity.

What caught my eye -- and Google's eye -- were the keywords "mechanical compromises" and "velocity" because that was the part of Matt Harvey's story that I was trying to understand better.

I asked Harvey then what it felt like on the days he brought his “A” game to the mound. “Power,” he told me. “It’s pretty exciting, knowing I can throw a 92 mph slider and start it down the middle and it ends up in the dirt. When I can reach back and run it up there at 98 and 99 when I want and drop a slider in there and throw a curveball for a strike and fade a changeup away to a lefty, it’s pretty fun.”

The phrase "reach back" also caught my eye because I have been updating my piece on the Power T and know it's a cue that is often associated with that potentially (extremely) problematic arm action.

Along the way, building upon the mechanics he learned from his father, Ed, who taught him to “show the ball to second base” on his arm swing, Harvey tweaked his mechanics to generate more velocity.

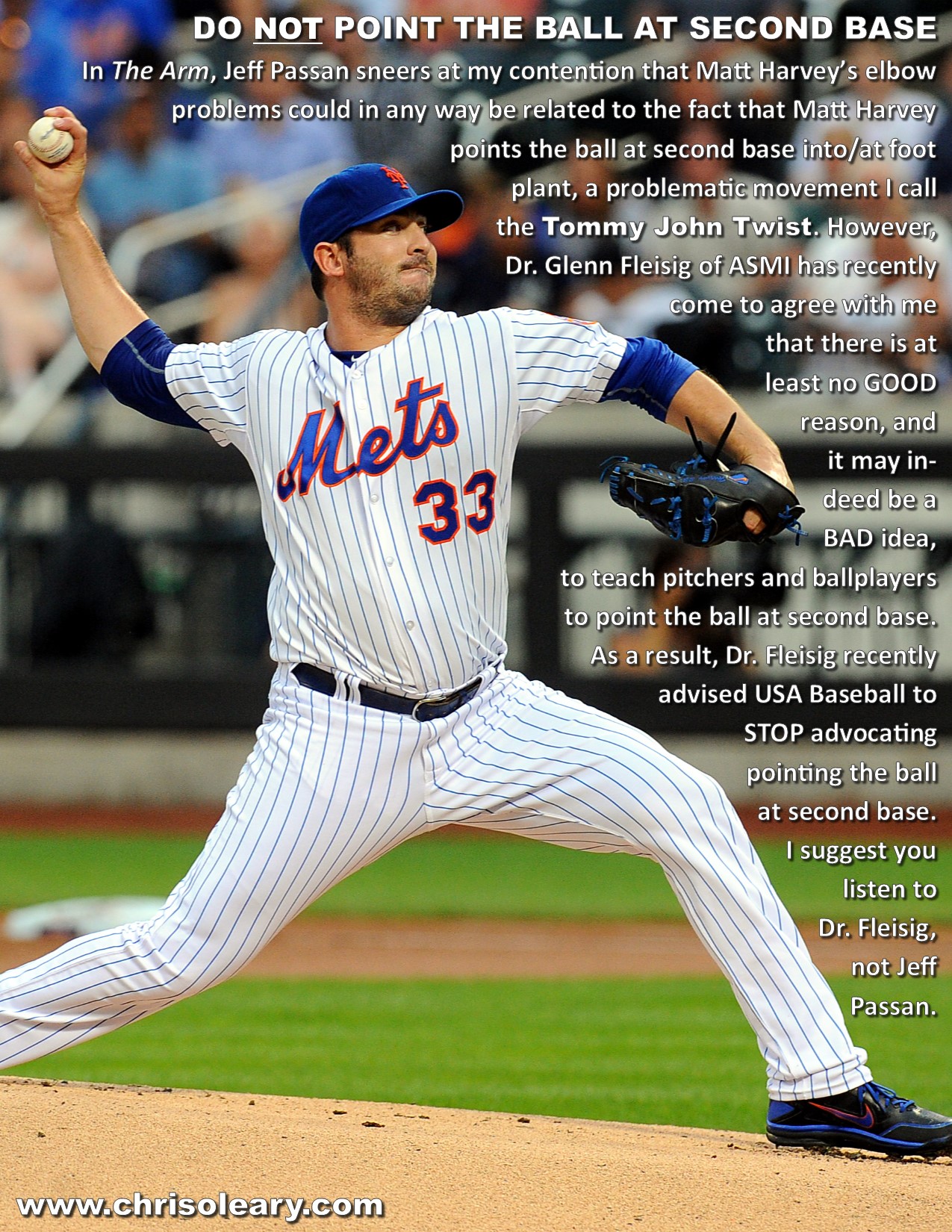

I have long suspected that Matt Harvey was taught to show (or point) the ball at second base, because that sure looks like what he's trying to do. In fact, this movement -- that I refer to in technical contexts as Premature Pronation and colloquially as the Tommy John Twist -- is something that is poo-poo-ed by Jeff Passan in The Arm.

Harvey and Verducci then make a point of doubling down on, and (tragically) restating the primacy of, pointing the ball at second base as a key to Matt Harvey's pitching mechanics.

“I’ve got the higher arm slot,” he told me, “so for me to get up and let my arm work I have to really stay back a lot longer and get my arm out a little sooner. At this point it’s natural. When I was learning, I always pointed to second.”

It is at this point that my ears perked up, because I realized Tom Verducci was discussing and using my words, concepts, and insights, but not my name.

Pointing the ball toward second base was commonly taught, though some pitching experts today believe it creates more stress on the shoulder and arm, preferring a right-handed pitcher, for instance, to “show” the ball more toward third base or shortstop in the load phase.

The "some pitching mechanics experts" Tom Verducci refers to? But not by name?

That's me.

I have written extensively about the problem with teaching pitchers (and position players) to point the ball at second base and why pointing the ball at second base is dangerous. I also put together a one-pager that explains the problem and illustrates it using Matt Harvey.

Do NOT Point the Ball at Second Base

I was the first, and to my knowledge am the only prominent person, who continually emphasizes the problem with pointing the ball at second base, which make it odd that Tom Verducci wouldn't name me.

What's more, this cue is central to why and how I got into the pitching mechanics business.

I was at a coaches clinic way back in 2005 or 2006 that was being put on by our baseball committee and that featured a number of coaches from a local high school (and my alma mater). One of the things they stressed was the importance of teaching pitchers (and position players) to point the ball at second base.

Because they emphasized it, and because it felt unnatural and weird to me when I tried it, after their presentation I went up to one of the coaches and asked him to explain it to me. I didn't know a lot about pitching, but I know that the way he described the throwing and pitching motion probably wasn't right. After I expressed my doubts, he told me, "Look at Nolan Ryan, Tom Seaver, Bob Gibson, and all the greats. They all pointed the ball at second base (or center field)."

So then I did this crazy thing.

I checked.

And I saw that they didn't.

Nolan Ryan, Tom Seaver, Bob Gibson, and most of the greats didn't point the ball at second base. Instead, they pointed the ball at third base (first base for lefties) or, at most, the shortstop.

I've written about this subject at length, from multiple angles, and I'm the only person that I know who has done so, at least to my knowledge, so I would appreciate it if Tom Verducci would stop with the "some pitching experts" and other "unnamed sources" crap and go ahead and tell people where he is actually getting his information.

Moreover, to get to his high arm slot, Harvey loads the ball far away from his head and so high that his right elbow gets higher than his shoulder, creating a stressful position known as elevated distal humerus.

But if you can throw a baseball 100 mph, where is the incentive to change? The incentive only comes with failure or injury, which have brought Harvey to this next phase of his career: the transition phase.

Finally, I have written at length about the problem posed to Matt Harvey and other pitchers by Hyperabduction and how it can lead to what I call Pitching-Induced Coagulation Syndrome.

Matt Harvey's Premature Pronation & Hyperabduction

However, I don't understand why Tom Verducci chose to use Ron Wolforth's term and not mine.

It's almost as if The is going out of his way to hide his (true) sources from people.

Stephen Strasburg

In 2011, Tom Verducci put together a piece that was clearly based on my

analysis of the pitching mechanics of Stephen Strasburg and Stephen Strasburg's problem with the Inverted W. However, either Verducci, or the person who quoted my

information to him pretty much word for word, never talked to me about it.

As a result, he didn't get it quite right.

While I discuss this topic at greater length in my new piece on injuries to pitchers, let me quickly go through Tom Verducci's piece and point out what he got right and what he got wrong.

Because his front foot lands too soon, Stephen Strasburg’s shoulder and elbow must bear a dangerous amount of force.

This is a perfect example of what happens when you borrow someone else's work without really understanding what you are borrowing.

The problem isn’t that Stephen Strasburg's front foot is early; that his front foot lands too soon. There’s nothing you can do about that because the front foot has to get down at some point. Rather, the problem is that Stephen Strasburg’s arm is late; his arm isn't in the correct position at the moment when his front foot heel plants and his shoulders start rotating.

As the picture below shows, at the moment Stephen Strasburg's front foot lands, and his shoulders start rotating, his Pitching Arm Side (PAS) forearm, instead of being vertical and at 90 degrees of external rotation, is pretty much horizontal and at 0 degrees of external rotation.

Stephen Strasburg

This is caused by the Inverted W in his arm action; it forces his arm to take a longer path to the high-cocked position and creates what is commonly known as a problem with rushing. As a result, his PAS upper arm will externally rotate especially hard and much, increasing the load on both his elbow and his shoulder.

But above all others one link of the chain is most important: the "late cocking phase," or the phase during which the shoulder reaches its maximum external rotation with the baseball raised in the "loaded" position (typically, above the shoulder) and ready to come forward.

The line above is very confusing, and reflects a problem with the conventional model of the baseball pitching cycle. The delineation between the early cocking and the late cocking phases of the throw are very ambiguously defined. It's one reason why I have come up with a simplified and revised baseball pitching cycle.

In addition, it's not correct that the shoulder is at maximum external rotation when the baseball is in the "loaded" or high-cock position. Instead, maximum external rotation occurs after the Pitching Arm Side forearm is vertical and the shoulders start to rotate.

Here's where things get REALLY interesting.

Here is the key to managing the torque levels in the late cocking phase: timing. The ball should be loaded in the late cocking phase precisely when the pitcher’s stride foot lands on the ground.

Verducci then goes on to say...

The problem is the timing associated with that move, not the move itself.

This is correct, but I feel like I've heard it before, perhaps when I said something remarkably similar about Mark Prior's pitching mechanics in late 2007...

This position isn't damaging in and of itself. However, by coming to this position, Mark Prior is ensuring that his pitching arm will not be in the proper position at the moment his shoulders start to turn.

As with pitchers with other timing problems like Rushing, because his pitching arm is so late, he will dramatically increase the stress on both his elbow and shoulder.

This can be verified using The Wayback Machine.

I say the same thing elsewhere on my web site...

(T)he Inverted W is not (that) bad in and of itself. The Inverted W doesn't directly lead to injuries. Instead, the problem with the Inverted W is that it can create a Timing problem...

...and...

The problem with the Inverted W is that it can (and I mean can and not always does) create a timing problem (aka rushing) and cause the arm to be late.

If you doubt what I said when, here's

The Wayback Machine's capture of this page from August 2008.

Tom Verducci then goes on to say...

Without the energy from the rest of the body, the shoulder and elbow must bear higher levels of torque in what in even optimum circumstances is a maneuver that taxes the physical limits of what an arm can bear.

“Without” should really be “Because of.”

The timing problem that can be created by the use of the Inverted W increases the energy, and thus the force, on the elbow and the shoulder, which can overload them.

I spoke with a key decision maker for one club last week who, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said his club will not consider any pitcher — by draft, trade or

free agency — who does not have the baseball in the loaded position at the time of foot strike.

I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the Mets. I have talked to people with them since 2007 and they have bought into my ideas.

However, once Strasburg takes the ball out of the glove, down and away from his body, his right elbow, not his right hand, literally takes the leading role. Like re-writing a script, the roles in the kinetic chain are switched. Now it is the elbow that raises higher than the shoulder and the hand.

This is correct.

There is one moment in this sequence when both of Strasburg’s elbows are higher than his shoulders, as if he were locked in medieval village stocks. Many people

have frozen that moment of his delivery and assigned it as the point of risk. That’s not entirely true.

The problem is the timing associated with that move, not the move itself.

OK, so Tom Verducci's clearly been reading my stuff. I say the same exact thing in my piece on the Inverted W...

(T)he Inverted W is not (that) bad in and of itself. The Inverted W doesn't directly lead to injuries. Instead,

the problem with the Inverted W is that it can create a timing problem

There's also this line

from my own web site where I say...

The problem with the Inverted W is that it can (and I mean can and not always does) create a timing problem (aka rushing) and cause the arm to be late.

I wish that Tom Verducci, or whoever he's talking to who is referencing my work, would just give me a call so that I can make sure that he gets this right. As it is, he's just confusing people and making this look muddier and more confused than it actually is.

When Strasburg gets his elbows above his shoulders and the baseball is below or about even with his right shoulder, his stride foot is hitting the ground. The ball should be in the loaded position at that point, but because Strasburg uses the funky “high elbow” raise, he still has to rotate his arm above his shoulder to get it there. The energy from landing on his stride foot has passed too early to the shoulder and elbow — before the joints are ready to use it.

Again, while this is mostly correct, the last line isn’t quite right. It’s not that this is an efficiency problem. Rather, because of the timing problem that is created by the Inverted W, his arm and shoulder aren’t in a good position to handle the forces that are generated by the rest of his body. As a result, instead of externally rotating smoothly, his PAS arm gets externally rotated especially much and hard (as happens to the last person in the chain in a game of crack the whip).

I asked Riggleman and Rizzo if they considered Strasburg’s mechanics put him at risk of injury and whether they intend to alter his mechanics when he returns to the mound. Neither one expressed much concern.

Strasburg’s shoulder is the next thing that is going to fail.

While this time off from throwing will probably buy him a few years, he is going to encounter major shoulder problems is he doesn't correct the problem with his arm action and his timing.

Rizzo did not draw a connection between Strasburg’s mechanics and his injury. He called the tearing of the ulnar collateral ligament “a freak accident.”

If I was a Nats fan, I would be nervous because Rizzo doesn't seem to understand how pitchers get injured.